PRESERVING THE STORY OF BIRMINGHAM FOR

FUTURE GENERATIONS

The Birmingham Civil Rights District

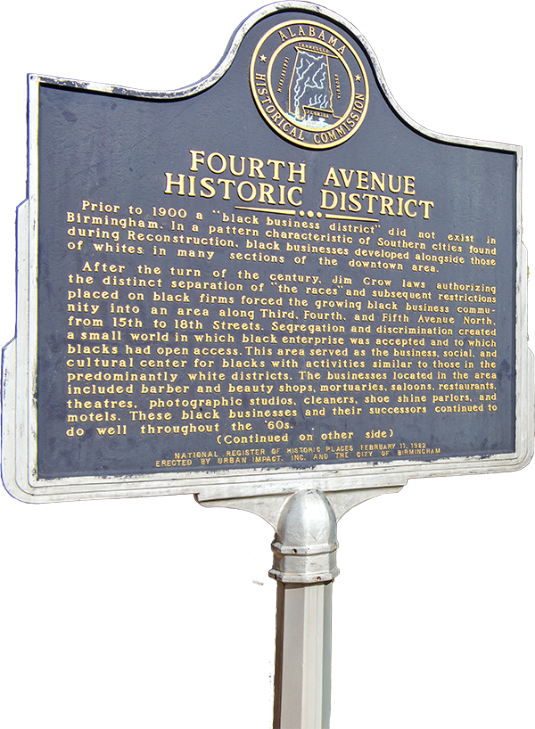

The Birmingham Civil Rights District, located in downtown Birmingham, encompasses a number of churches, businesses, and other gathering places that played a fundamental role in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Many of these sites are within walking distance of one another.

The District encompasses a museum and educational institute; several churches and a motel, all of which played a major role in the Birmingham campaign; and a neighborhood that was the center of Black business and social life in the city, which includes several historic buildings awaiting their chance at refurbishment.

Several of the sites are part of the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, a collaborative partnership between the National Park Service and the City of Birmingham. The Birmingham Civil Rights District website is organized to help visitors discover how to experience these historic sites virtually and in-person tours.

“If you come to Birmingham, you will not only gain prestige but really shake the country. If you win in Birmingham, as Birmingham goes, so goes the nation.”

– Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth

The city was also home to the Black Barons, a Negro League baseball team that counted legends such as Satchel Paige, Willie Mays, and William Henry Greason among their players.

“I wish you had commended the Negro demonstrators of Birmingham for their sublime courage, their willingness to suffer, and their amazing discipline in the midst of the most inhuman provocation. One day the South will recognize its real heroes.”

– Dr. King, Letter from Birmingham Jail